Racism in the Supermarket Aisle: The History and Future of Ethnic Mascots

Aunt Jemima fits a white narrative.

Racism in America is so widespread that most of us have been dropping tokens of it into our supermarket basket for decades without batting an eye: brands like Aunt Jemima’s, Uncle Ben’s, and Cream of Wheat, all of which boast racist mascots, some of which are over 100 years old.

This behavior is not a willful admission of racism by any means. Rather, it speaks to the indoctrination of White America, starting with some of our earliest experiences. It may seem almost inconceivable that something as mundane as breakfast cereal could be perpetuating the suppression of millions of Americans, but there’s perhaps no better medium for hiding those cues than in plain sight: the food we grew up on, the food many of us now feed our own children.

As protests continue around the country demanding justice for the Black men and women killed by police, like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, longstanding supermarket brands are finally taking a look at their branding, and many are choosing to make a long-overdue change.

How Did Racist Mascots Last So Long, Anyway?

Aunt Jemima’s story may shed some light. In the late 1800s, Chris L. Rutt, a Missouri newspaper editor, named his new flour brand “Aunt Jemima” after a minstrel song. Jemima’s likeness was a “mammy”—the smiling, happy slave that served white families. Nancy Green, the woman who portrayed Aunt Jemima in the first advertisements and logo, was herself a former slave.

The use of the term “Aunt” (and, for that matter, the “Uncle” on “Uncle Ben’s,”) wasn’t familial. Rather, it was a term used for elder slaves that often worked in homes instead of the fields. Using the word “aunt” and “uncle” in place of “Mrs.” or “Mr.” lowered their status with their masters.

The Aunt Jemima brand is now mostly known for its syrup, but it started out as a quick-rising flour, mainly used for pancakes and biscuits. Its popularity exploded, and by 1915 it was one of the most well-recognized logos in the country. It even changed trademark laws to help protect its iconic mascot. Early versions of the Aunt Jemima flour packaging included paper doll cutouts for children that showed Jemima and her family barefoot in old, tattered clothing with an option to make them over in nicer outfits as part of the rags to riches story, further elevating the white savior narrative. Their success only came at the hands of the white founder and customers.

“The character of Aunt Jemima is an invitation to white people to indulge in a fantasy of enslaved people — and by extension, all of Black America — as submissive, self-effacing, loyal, pacified and pacifying,” Michael Twitty, culinary historian and author of “The Cooking Gene,” wrote for NBC News. “It positions Black people as boxed in, prepackaged and ready to satisfy; it’s the problem of all consumption, only laced with racial overtones.”

White privilege extended into then-parent company Quaker’s positioning of the brand in some of its first television commercials. It sponsored the famous 1950s family show “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.“ The Aunt Jemima spot breaks feature a white well-to-do husband and wife lazily cooking up a weekend breakfast, and scores of other commercials for the brand throughout the decades feature noticeably all-white casts.

Aunt Jemima isn’t the only racist mascot in the syrup aisle. While Jemima is known for her big smile and headscarf, Mrs. Butterworth is all about the bottle, the shape of which resembles a mammy dress.

“Critics have long associated the shape of the Mrs. Butterworth’s bottle with the mammy, a caricature of black women as subservient to white people,” Maria Cramer wrote for Business Insider. ConAgra, Mrs. Butterworth’s parent company, is now working to update the bottle.

If it seems like racist mascots bend heavily toward breakfast staples, there’s a reason. Slave-owning white families woke to warm breakfasts, prepared for them while they slept. It was more than convenient; it was indulgent. And after slavery ended, corporations stepped in to profit off of that expectation. The Black mascot-led product packaging wasn’t targeting Black consumers. Rather, they were being used to fit a white narrative about Black people, says Twitty.

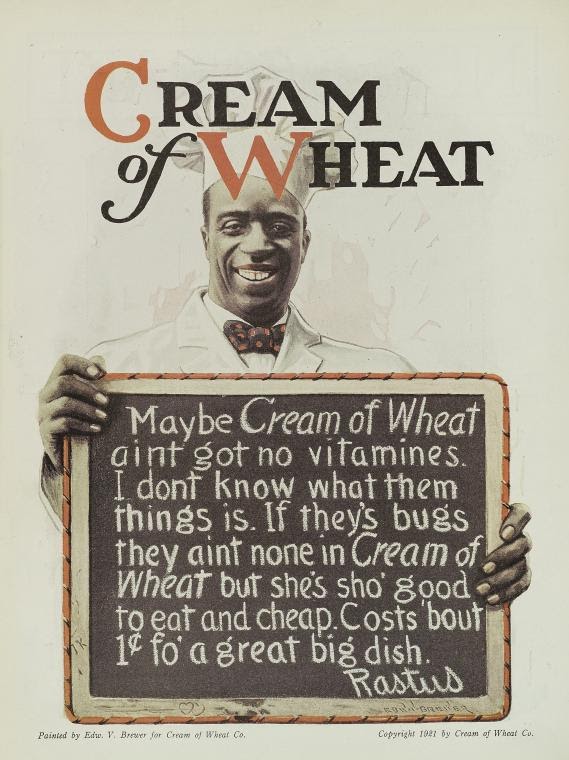

“Rastus — pictured standing stiffly with his pot cleaned and his tray brimming with Cream of Wheat in the other hand, grinning as Thanksgiving turkeys strutted by — was meant to be proof to white shoppers that, much like faithful old Rastus, their product would not take from you but be ever at your service, ready to give without limit, and never give in to the temptations of the market to defraud the buyer.”

Because brands quickly become iconic, they become big moneymakers, too. The multinational corporations who eventually gobbled these brands up looked then as they do now to numbers over anything else. Bottom lines dictate the staying power of logos, mascots, and those stuck-in-your-head-forever jingles and taglines. Keeping shareholders happy is a bit like checking on a sleeping baby: if they’re still laying there peacefully asleep, back out of the room quietly.

But that’s the problem. Being beholden to investors instead of morality and common decency desensitized generations of Americans to the concept of Black inferiority because corporations didn’t want to risk dipping into the red.

Much like the football team formerly known as the Washington Redskins took decades to remedy its racist name (now a work-in-progress, as the club is temporarily rebranded as the “Washington Football Team”), these iconic food brands have also dragged their heels for decades, looking the other way instead of taking the lead in reshaping the narrative around race in America.

And some brands still aren’t as willing to take responsibility, yet.

Trader Joe’s Defends Ethnic Mascots

Supermarket chain Trader Joe’s was recently urged to do away with its in-house ethnic labeling. Currently, Latin offerings are marketed as Trader Jose’s, Italian food is labeled as Trader Giotto’s, and Asian items are sold under the monikers Trader Ming’s and Trader Joe San.

“The Trader Joe’s branding is racist because it exoticizes other cultures,” wrote high school student Briones Bedell, who started a petition urging the store to rebrand the items. “It presents ‘Joe’ as the default ‘normal’ and the other characters falling outside of it.”

“The common thread between all of these transgressions is the perpetuation of exoticism, the goal of which is not to appreciate other cultures, but to further other and distance them from the perceived ‘normal,’” she continued.

The discount supermarket chain’s initial response to the petition signaled it would be making a change to its labels, much like numerous other brands.

“While this approach to product naming may have been rooted in a lighthearted attempt at inclusiveness, we recognize that it may now have the opposite effect — one that is contrary to the welcoming, rewarding customer experience we strive to create every day,” company spokeswoman Kenya Friend-Daniel said at the time.

But it has since backpedaled on changing the decades-old names.

“We want to be clear: we disagree that any of these labels are racist,” a statement posted to its website read. “We do not make decisions based on petitions.”

Trader Joe’s says customers like the names and resonate with them.

“We thought then — and still do — that this naming of products could be fun and show appreciation for other cultures,” the company added.

But Bedell says even the chain itself was founded on racist stereotypes. Based on the origin story on Trader Joe’s website, the chain’s floral South Pacific decor and themes were inspired by the 1919 Frederick O’Brien, book “White Shadows in the South Seas,” which tokenized “exotic” people of the South Pacific. The chain also cites the Disneyland Jungle Boat Cruise, which visits riverbanks populated by exaggerated characterizations of native people.

Bedell says both the book and the Disney ride perpetuate racist stereotypes as well as furthering the white savior narrative. Trader Joe’s stores are also most commonly located in well-to-do white suburban neighborhoods rather than Black communities.

“It’s intended to allow the consumer to build up this perceived sophistication through their knowledge of worldliness through their choice of food,” Bedell told the Associated Press. “But it’s not a cultural celebration or representation. This is exoticism. These brands are shells of the cultures they represent.”

But even if Trader Joe’s is currently defending its labels, consumer-driven change is happening in the marketplace, and it’s unlikely we’ll still be seeing “Trader Jose’s” on tortilla chips 100 years from now. Consumers are now supporting Black-owned businesses (check out this list here) more than ever before. And they’re also supporting brands taking the steps to do away with racist mascots or brand names.

As consumers support brands more in line with their values, perhaps we are paving the way toward a grocery store that feels inclusive to all.

Related on Organic Authority

This Compton Native is Bringing Vegan Soul Food Home

Junk Food Ads Target Black Children, New Study Shows

Seed Company Sold Bad Seeds to Black Farmers on Purpose, Says Discrimination Lawsuit